Where Are All the Exceptional South Asian Restaurants?

One writer’s search for distinctive, regional South Asian food in a city that's starved for it.

Shona Sanzgiri is a writer, photographer, and editor at Apple. He was born and raised in the Bay Area and has lived in Los Angeles for the past four years. Shona started his journalism career in local news at the Mercury News, Santa Cruz Sentinel, and San Francisco Weekly. He's also written about thrift-store shopping in L.A. with public radio host Jesse Thorn for GQ, sent travel dispatches from Cuba and Oaxaca for The Paris Review, and profiled one of Mexico's only female bullfighters for VICE. He and I first started talking about this story—an Indian American’s journey to finding the best regional South Asian food in L.A., digging into why there’s such a dearth of it to begin with—last year, and I’m excited to share it with you all today. –Emily Wilson

Photographs by Shona Sanzgiri

To say that Los Angeles has great Asian food isn’t just an understatement—it verges on cliché. The city is a sprawling constellation of strip malls and storefronts where you can chase balloon-sized soup dumplings, Hainanese chicken, or the perfect tahdig any night of the week. Its map of enclaves—Koreatown, Thai Town, Little Tokyo, Tehrangeles, the SGV—reads like a roll call of the continent.

But for all the ground L.A. covers, one region hardly registers: South Asia. There’s Little Bangladesh and Artesia, of course—scattered, tiny pockets that feel more like afterthoughts than anchors, with restaurants and businesses that haven’t exactly evolved or even held onto the South Asian base they once served.

Elsewhere in the city, there are Indian restaurants in the broadest sense, places stuck in culinary limbo that serve the same greatest hits lineup of (typically) Punjabi standards: butter chicken, chicken tikka masala, saag paneer, daal tadka, maybe a token South Indian dosa. The flavors arrive dulled by repetition, thickened into edible complacency. It’s a predicament that’s kept South Asian food confined to a narrow script, flattened and monolithic, offering little in the way of what makes it so unique: its staggering regionality.

“I would love to see someone open an incredible Goan restaurant, or chaat spot, or a place that really just specializes in dosa and uttapam and nothing else,” says L.A.-based food writer and former Food & Wine editor

, whose cookbook Amrikan: 125 Recipes from the Indian American diaspora, reflects both the regionality and evolution of South Asian cooking. “Most Indian restaurants [in Los Angeles] feel the need to have Cheesecake Factory-size menus where they do it all, but in trying to do it all, you lose the magic.”The flavors arrive dulled by repetition, thickened into edible complacency. It’s a predicament that’s kept South Asian food confined to a narrow script, flattened and monolithic, offering little in the way of what makes it so unique: its staggering regionality.

Growing up Indian-American in the Bay Area, I was surrounded by such regional, eclectic, and even experimental South Asian restaurants but mostly ignored them, arrogantly assuming there was little value in spending money on something I thought my mom could cook better (while committing the same sin of lumping the entire subcontinent’s cuisine together). Eating out was for chasing what I mistakenly considered sophisticated—or at least expensive, money being a lazy shorthand for good taste to a naive young striver—like French bistros, Japanese omakase, or self-serious “New” American places with menus printed in lowercase. Turns out, my internalized bias was at least partially the byproduct of being raised in the U.S.

In his book The Ethnic Restaurateur, New York University professor of Food Studies Krishnendu Ray argues that a “global hierarchy of taste” shapes how certain foods are valued in the West. I’d absorbed this idea uncritically, deferring to how food media—particularly the vaunted Michelin Guide, which took 101 years to award a single star to an Indian chef—seemed to treat South Asian food as a colorful novelty, but not fine dining.

Some of my indifference came from internalized self-loathing, but it was also shaped by experience. South Asian food, as I knew it, was modest—mostly vegetarian, rarely eaten out, and never precious. At home or in the subcontinent, meat was an indulgence, not a staple. We only went to restaurants when my mom was too tired to cook or when a dish called for tools we didn’t have, like a tandoor, or techniques she hadn’t mastered: layered Hyderabadi biryani, vada pav (a fried potato puck in Portuguese-influenced bread), or the dessert puran poli, a jaggery and chickpea-stuffed flatbread usually reserved for festivals. These were complex, deeply satisfying dishes, but they were meant to be eaten with your hands, sometimes standing, often on the go. They didn’t fit the Western blueprint of “fine dining,” with its cutlery choreography, formality, and performance of cultural capital.

South Asian food has been relegated to a lower rung of prestige (ironic given that centuries ago spices were worth more than their weight in gold) due to racial and class dynamics, social status, global economic standing, and what Ray calls “the $30 ethnic price ceiling,” where consumers perceive the value of so-called “ethnic” dishes as never surpassing $30. Diners might routinely pay upwards of $40 for the contradictorily rustic, simple “peasant” food of France, Italy, or Japan (I mean, have you seen entree prices lately?) that carry an aura of refinement, high technique, and worldliness, but balk at the same price for labor-intensive, ingredient-rich curries.

As a result, the South Asian restaurateurs I spoke to for this story all expressed the same concerns over raising prices, worried about losing loyal customers as well as new ones—despite widely reported increases in labor costs, food costs, and inflation over the last several years.

Compounding these fears is the reality that, in much of L.A., South Asian restaurants often stand alone, expected to represent the entire subcontinent. “We don’t have strong enclaves like Koreatown or Little Tokyo and Sawtelle or Chinatown where businesses can draw in people and support one another as an ecosystem,” Shah explains. So spread out is the South Asian population here, in fact, that New York Times food critic at large Tejal Rao’s favorite Indian restaurant isn’t in L.A., but 90 minutes north in Bakersfield.

This distance calls to mind revelatory South Asian meals I'd had in even more distant places, like New York City, where the aptly named Unapologetic Foods group claims to have cracked open conventional ideas concerning Indian cuisine. The confidence isn't misplaced: the diverse range of restaurants run by restaurateur Roni Mazumdar and chef Chintan Pandya, including Dhamaka (bold, provincial flavors), Adda (home-style cuisine), and Rowdy Rooster (Indian fried chicken) are wildly popular. At Semma, their restaurant devoted to Southern Indian fare, Shah had an “incredible experience not knowing what 75% of the items on the menu were.” The Indian food world icon Padma Lakshmi counts amongst Unapologetic Foods’ fanbase as well, once having leaped to their defense in response to a disrespectful review.

All of this got me thinking: despite L.A.’s lackluster South Asian food scene, where in town could I, an Indian American with a roving palate, go to eat dishes that were at once familiar but could jolt me out of my own complacency, places I might fiercely defend?

Mayura

Inside Mayura, L.A.’s only Keralan restaurant, there’s little to suggest that I’m about to have one of the best fish curries of my life, but there are some indications.

One is its legacy: a constant presence on Jonathan Gold’s 101 Best Restaurants list, often as the lone Indian entry. Kerala, unlike much of India, was never ruled by the Mughals, the Indo-Persian empire with roots in Central Asia, whose cuisine came to define Indian food abroad. That Gold championed not just an Indian restaurant, but one rooted in a region often overlooked even within India, spoke to his famed precision and palate. Unlike North India, where the food is characterized by meat, wheat, dairy, and spices like garam masala and saffron, in Kerala, ingredients like coconuts, dried curry leaves, tri-color peppercorns, and tamarind reign. Here, Hinduism preserved many of its ancient traditions, like Ayurveda, the holistic system of medicine that's influenced Kerala's diet with its emphasis on light, fresh, seasonal whole foods.

The other indication is the makeshift gallery of visiting celebrity photos that line the wall by the buffet. As co-owner Dr. Padmini Ayani leads me to a table, I scan the faces: Dev Patel, Hillary Clinton, Wolfgang Puck, Mindy Kaling, a parade of Bollywood stars. Normally, I find this practice tacky, a dubious way to signal quality by way of celebrity endorsement. But I’m also intrigued, given the number of South Asian stars, some of whom I’m told raced to Mayura after landing at LAX.

I take a seat and browse the massive menu. Sensing my indecisiveness, Dr. Ayani takes the menu from my hand, beckons the server, and orders on my behalf. In minutes, a cup of chai arrives, then a massive dosa with lacy edges. It’s excellent, but no match for the main event: the Kerala fish curry.

The fish, which is Pacific salmon instead of the usual Indian mackerel or sole, is coated in an amber-colored sauce of tangy tamarind and red chili that cuts clean through the coconut milk’s richness. Next to the curry sits a short stack of appams, soft, spongy rice-flour pancakes with a sour tang, to absorb any leftover curry. Creamy and fragrant with fresh coconut and a blend of spices Dr. Ayani won’t name, the curry is unlike anything I’ve had, a far cry from the recycled mother sauces that prop up most Indian menus. What she will tell me is that she sources those spices directly from Kerala, where no two fish curries are alike, owing to the nearly 160 species of fish found in the state’s freshwater fisheries, lakes, rivers—and its perch at the southwestern tip of the Malabar Coast, where the Arabian Sea meets the Indian Ocean and the rains fall hardest in the subcontinent.

A teacher and businesswoman by training, Dr. Ayani and her husband, Aniyan Puthanpurayil, moved to Los Angeles from Kerala in 2003 and opened Mayura within two years. For Puthanpurayil, a third-generation restaurateur, the kitchen was destiny. Hers? Managing the front of house, armed with warmth and business acumen. “Combining theory with practice,” she says.

But given L.A.’s relative unfamiliarity with Indian food, opening a Keralan restaurant was a gamble. “I love risk,” she laughs. The space had once been a Pakistani restaurant; remodeling it and building a new audience took time. At first, the couple handed out flyers, emailed local schools, and catered office parties—until Jonathan Gold walked in. “One day I saw all these people holding newspapers,” she recalls. His LA Weekly review changed everything.

Last February, Mayura expanded next door with Navaa Bistro, their smaller, more casual, supposedly contemporary sister restaurant that serves a curious bifurcated menu of street food with a superficial California twist (think paneer tikka wrapped in lettuce leaves) alongside even more esoteric Keralan dishes, like a chicken biryani from the maritime port of Thalassery, where Arab, Persian, Dutch, and Syrian Jewish flavors mingled with northern Keralan. There’s also an extensive Indo-Chinese menu that includes the addictive gobi manchurian, fried cauliflower florets slicked with what tastes like ketchup, and a handful of random North Indian dishes too.

A little confused, I ask Dr. Ayani about the change. “We want to please our customers. We cook our North Indian food in a separate kitchen out of respect.” She pauses to hug an outgoing guest before looking back in my direction: “Here, as in India, the guest is god.”

Baja Subs

At the northern terminus of the 405 in Northridge, I find myself even further south on the subcontinent—at Baja Subs, a Sri Lankan restaurant and convenience store, lured by the promise of a very different fish curry. A modest store flanked by a tire shop, Baja Subs is owned by Premil Jayasinghe, an alumnus of California State University, Northridge, who took over the lease of the compact space in 2013. Within months, business was booming.

“There are thousands of Sri Lankans in the area,” he tells me, as I stare down an intimidating bounty that covers the small table. I start with the lamprais: a parcel of mutton curry, ash flower plantains, turmeric rice, a chicken patty, fried egg, and a gooey brick of caramelized onion relish, all wrapped in banana leaf and baked. Brought by the Dutch from Indonesia (a similar version can be found at the Balinese pop-up Bungkus Bagus), lamprais—lomprijst in Dutch—is, according to writer Vidya Balachander, the “fragile thread” keeping the mixed-race Dutch Burgher community from fading away.

Next to the unfurled leaf sits a tub of bone-in chicken biryani crowned with pineapple chutney, a container of chili-powder-laced, freshly grated coconut flakes, and a dry ash root plantain sambal that’s halfway between chutney and chili crisp. Then comes the signature: tuna, meaty and rich, simmered in a deeply browned curry, served with string hoppers, rice flour noodle pancakes to be dredged through sambal and dunked into a divine broth of coconut and turmeric gravy. I can’t stay with one dish. I mash and mix everything into a sublime study in contrast of culture, memory, and Sri Lankan history.

It’s Sri Lankan New Year, and a steady stream of customers pours in to pick up takeaway and exchange greetings. A blur of Sinhalese, English, and sometimes even Spanish fills the air. In the kitchen, a trio of cooks moves in perfect sync. One of them, Kumar (who didn’t want to share his last name), has worked with Premil for years. He kneads and stretches dough into roti while another cook stirs several pots of curry with one hand and shakes a wok of noodles with the other. They take turns at the griddle, flipping soft buns baked in the Portuguese style found along the South Asian coast, stuffed with meat or vegetables, then fried. In the dining room, Jayasinghe paces behind the buffet counter, answering phones and watching the lunch crowd roll in. On weekends, the restaurant really sings, offering more dishes, including hoppers glued together with fried eggs.

The market portion of Baja Subs, Jayasinghe says, helps offset rising costs. The counter is flanked by racks of Funions, Fuego Takis, sour candies, Swisher Sweets, tall cans of Modelo, and Sri Lankan coconut water. “I can’t raise prices,” he sighs. “Right now, my profits are being eaten away. But the restaurant is doing well,” he gestures toward the room full of familiar faces. “Someday, I might open in Artesia.”

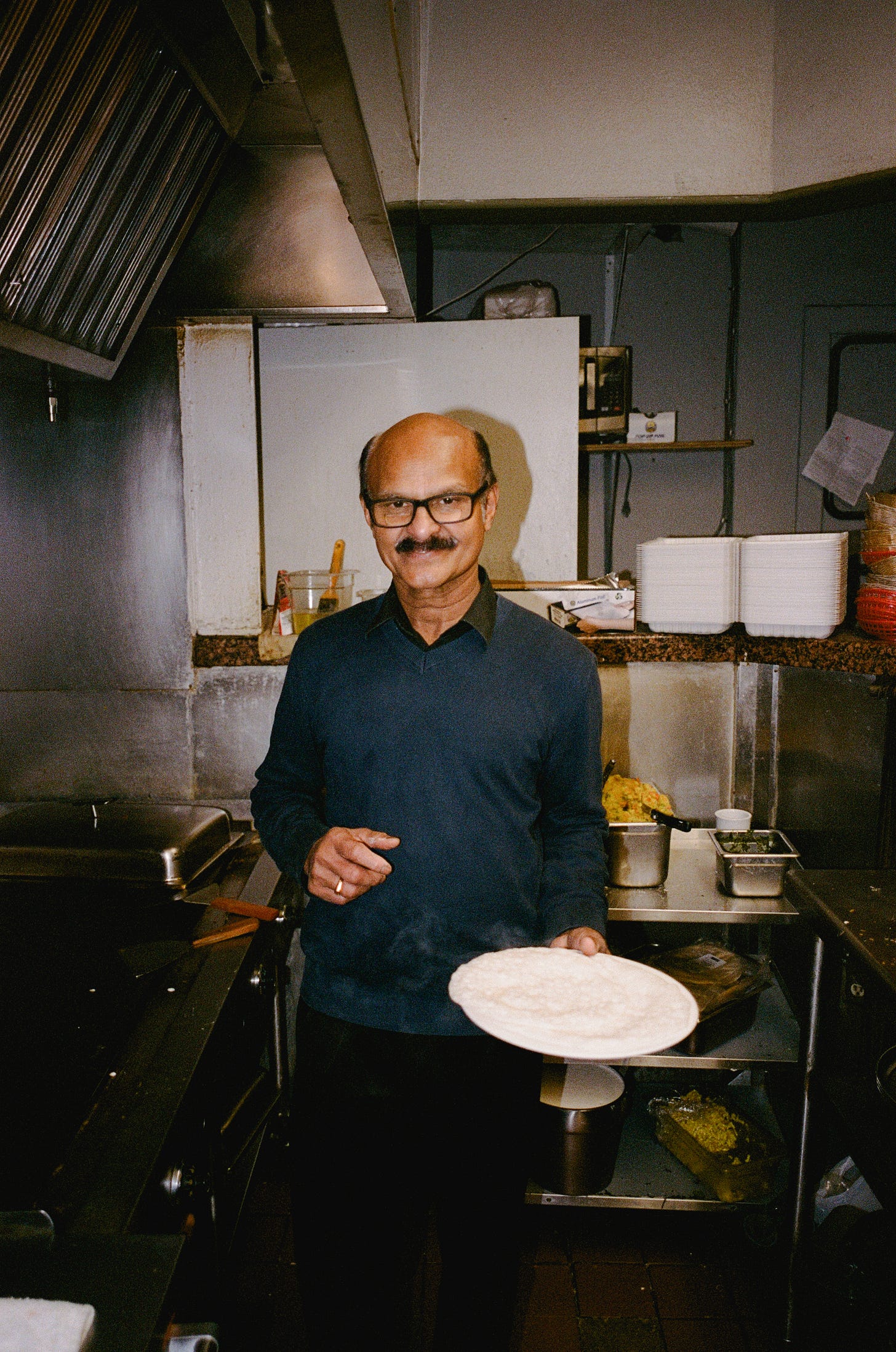

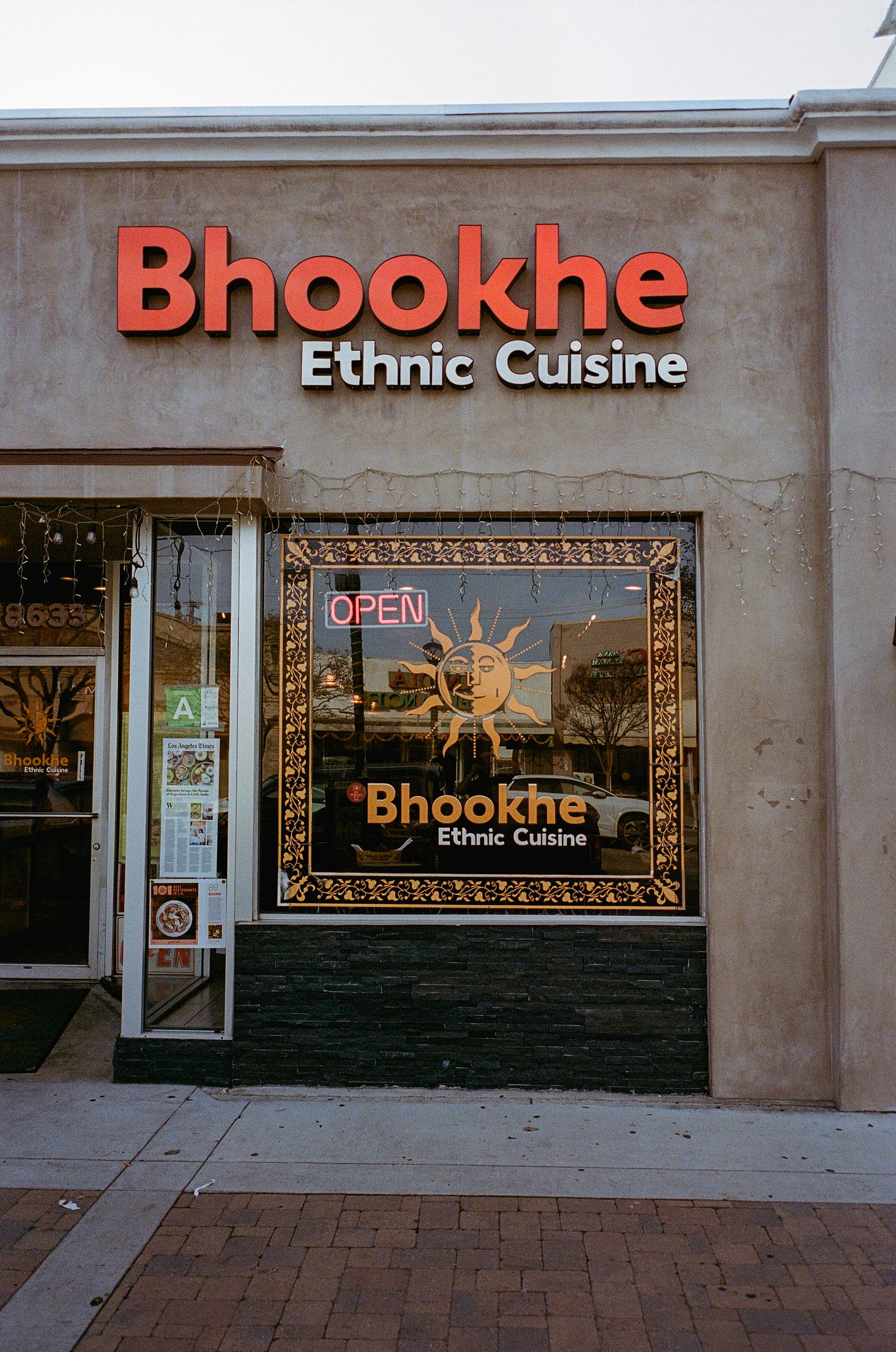

Bhookhe

Walking along Artesia’s Pioneer Boulevard, the spine of L.A.’s only Little India, is a culinary tour of the subcontinent in a few short blocks: Punjabi curries, Gujarati thalis, Mumbai street food, even a chai shop that serves paan, the betel leaf digestive spiked with spices, slaked lime, and sometimes tobacco.

Smack in the middle sits Bhookhe (Hindi for “hungry”), a vegetarian Rajasthani restaurant that Los Angeles Times critic Bill Addison called one of his favorites of 2023. It was an inspired pick, especially given how little-known Rajasthani cuisine is outside India. Home to the subcontinent’s only major desert, Rajasthan’s food leans on ingredients that thrive in its harsh climate: grains, lentils, dairy, and meat, often cooked over open flame—fuel for the region’s once-nomadic shepherds and warriors. And yet its cities are some of the most vivid in India, kaleidoscopic with color, forts, and palaces.

Bhookhe captures these twin poles best in its majestic maharaja thali—a royal spread of house-made flatbreads, pickled vegetables, spiced yogurt, and silky, deeply flavored curries unlike anything else in L.A. Each thali comes with chaas, a savory buttermilk drink spiced with roasted cumin and green chili. As a child, I hated it—thrown by the savory notes and mustard seeds bobbing on top. Now, I love it. Cool and spicy, the taste lingers, and I finish it swiftly.

No space on my thali is unclaimed. It’s a mosaic of many small dishes, including mounds of rice and chutneys, dal, and raw vegetables. Six spheres of grain are squeezed together: the baked wheat orbs called batis; churmo, a sweetened, mashed-up roti layered with ghee and jaggery; and one even sweeter—the mawa ri kachori, a blistered shell of flour and ghee stuffed with condensed milk and nuts, the building blocks of most Indian desserts. A ring of condiments completes the circuit: red, green, and wild cucumber chutneys, plus two small bowls—one of raita topped with fried chickpeas, the other pure ghee. The breads, twisted and rolled into various shapes, are torn, dipped, dragged, and dunked through dishes laid out on dried sal leaves. Each swipe reveals something new: heat, funk, brightness, a whisper of sweetness. Every bite recalibrates my conception of Indian food.

Delighted but defeated by the sheer quantity of food, I pause and talk with co-owner Anshul Dwivedi, who opened Bhookhe with his wife, Pooja, after the pandemic upended his career as a gemstone jeweler and day trader. He had lost everything and was struggling to pay his children’s tuition—until he proposed a third venture: a restaurant.

Each thali comes with chaas, a savory buttermilk drink spiced with roasted cumin and green chili. As a child, I hated it—thrown by the savory notes and mustard seeds bobbing on top. Now, I love it. Cool and spicy, the taste lingers, and I finish it swiftly.

At first, it was just the two of them. “I was coming in at 5 a.m., cleaning restrooms, shopping, cooking. Then my wife came to help and I quickly realized she’s the better cook,” he says. Early days were rough. “We couldn’t find cooks who knew Rajasthani food. They’d only cooked Punjabi or South Indian. Rajasthani? Blank,” he says.

Though Bhookhe offers some non-Rajasthani fare, like pav bhaji, the Dwivedis refused to pivot. “When you’re trying to please everyone, you’re pleasing no one,” he says. “No one else was doing this. I told myself, if people don’t like it, we’ll close. But what if we succeed?”

Literally went on my computer and created a profile so I can shout from the comments: I KNOW WHERE IT IS: Bakersfield!!!

Sorry, but also not sorry. We usually drive to LA to eat, not the other way around, but Bakersfield takes the cake here. We have a huge Sikh population here (one of the biggest outside of NYC and DC)! We even have billboards in Punjabi. Specifically, the south/ southwest areas of town. We actually have a ton of options. A lot is your common 'american-friendly (not americanized*, there's a difference IMO), but we have a real variety if you know where to look. Punjabi Dhaba is the best north-indian food I've had, ever. Worth the visit!!!!!!!!

chargha house in Culver City was recommended to me by a Pakistani uber driver and consistently is delicious.