At Culinary Bookstore Prospect, You're Bound to Discover Something

Mark Aquino deals in rare and special books at the intersection of art, design, and food.

Photographs by David Gurzhiev

I have a cookbook problem. I love reading them, looking at them, and cooking from them (especially now that I’ve made my collection searchable and thus more accessible to use, thanks to Eat Your Books), so I love buying them. We recently got new bookshelves, and I’ve already outgrown my allotment for cookbooks. In the last year, however, my cookbook-amassing habit has evolved. Instead of perpetually visiting shops like Chinatown’s Now Serving and Brooklyn’s Archestratus to purchase the new titles I’m drawn to, I’ve been honing what you might call a collector’s practice. When David and I travel, we’ll visit used bookstores. He’ll camp out in the photography and art section while I’ll make myself comfortable nosing through the food books. This shift parallels how I think of visiting restaurants nowadays, too: it’s fun to check out new places, but there’s more to learn from the spots that people have been frequenting for five, ten, or fifty years.

Old cookbooks don’t always age well, particularly American cookbooks. American cuisine has evolved significantly alongside American language and culture over the past half-century. Still, cookbooks offer unparalleled insight into the aesthetics and lifestyles of the times in which they were published. It’s unlikely that I’ll ever cook from the Woman’s Day Collector Book (1960) I found at a dusty shop in Sante Fe. Yet the recipes within it (Raised Sally Lunn, Spiced Ham and Bananas, Jellied Tomato Madrilène) and the way it’s written (appetizers are described as “hot and cold canapés to tease the eye and taste buds”) tell me a lot about what housewives were up to 64 years ago. Cookbooks are pieces of cultural history and are thoroughly entertaining as windows into past eras.

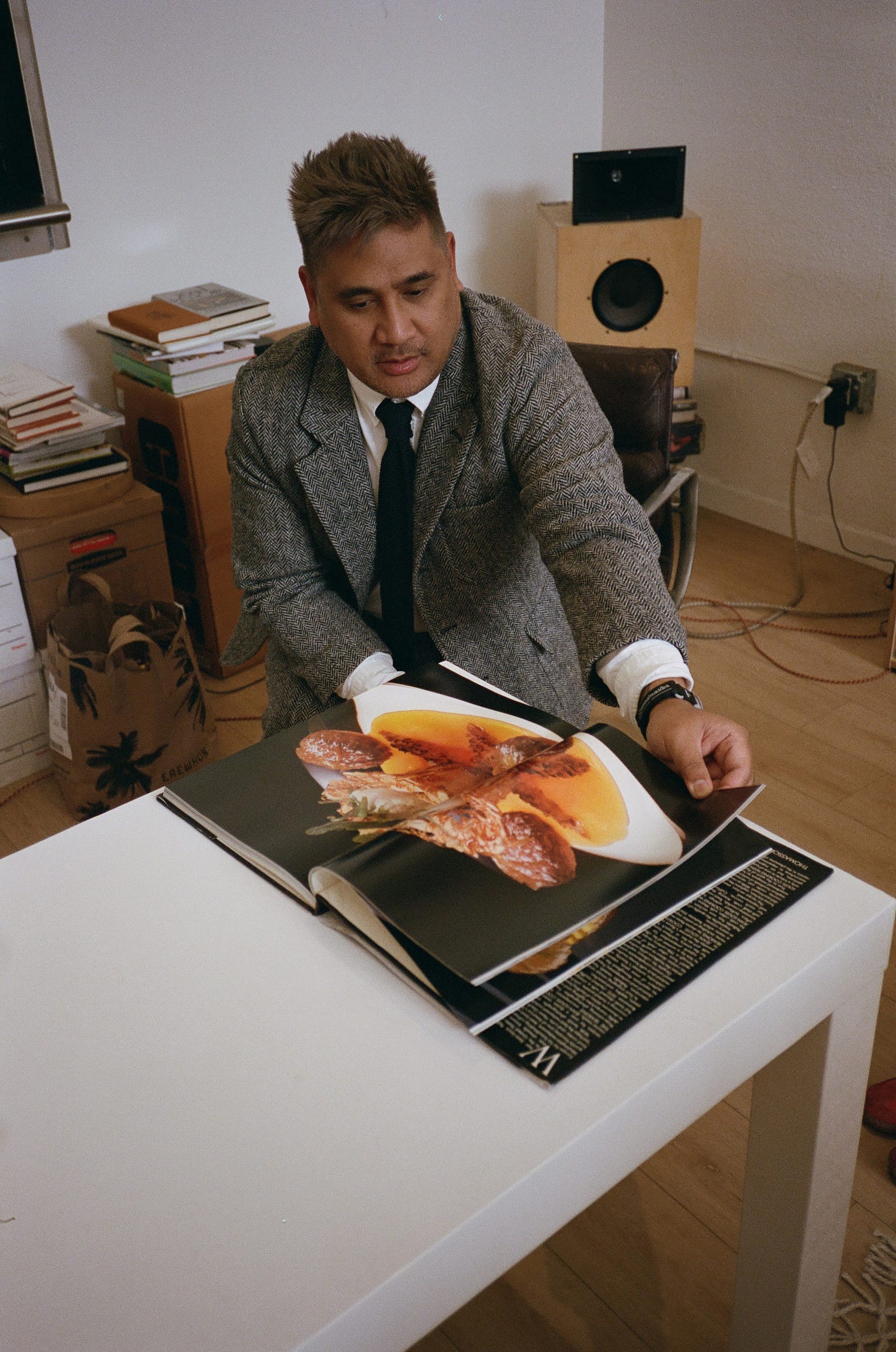

“I’m a sucker for ‘90s cuisine,” says Mark Aquino, the owner of South Pasadena’s art and design-focused culinary bookstore, Prospect. “I know it gets a bad rap, but I have Gourmet magazines from the ‘90s that are excellent. Some of it is a little problematic nowadays. It’ll call Chinese cuisine ‘exotic,’ [for example]. But this is the stuff that was aspirational to me, growing up in the ‘90s.” At Prospect, a tall pile of now-defunct Gourmet magazines sits in the window display, while the complete collection (all 24 volumes) of Lucky Peach is up for grabs on a table for $800. Other titles in the shop range from a facsimile of fashion designer Christian Dior’s 1972 aluminum-embossed La Cuisine Cousu-Main to a retrospective of paintings book by the artist Wayne Thiebaud (with his signature painted cakes on the cover) to a signed first edition of Anthony Bourdain’s Les Halles Cookbook from the early aughts ($318). On a recent visit, I picked up a copy of Michael McCarty’s Michael's Cookbook (1989) and The Wolfgang Puck Cookbook (1986) to add to the Los Angeles section of my cookbook collection.

Prospect carries mostly vintage books in mint condition, many of them first editions and/or signed, and some newer titles. Aquino’s curation tends towards the intersection of art, design, and food, but “I do play fast and loose with the term culinary arts,” he says. “There are a lot of books on the periphery, too. It’s really wherever I want to take it.”

Aquino was born in San Diego to Filipino parents who were excellent home cooks. His dad was a cook in the Navy. “I remember seeing my dad butcher a fish and then use the innards in compost for his garden,” he says. Growing up in a no-waste household is likely why Fergus Henderson’s offal-focused Nose to Tail Eating: A Kind of British Cooking (1999) is one of his prized possessions. The most important book in his personal collection, also from 1999, is the first he acquired: The French Laundry Cookbook. Aquino started seriously collecting cookbooks while in college in Santa Barbara, where he also worked at Borders. “I couldn’t eat out all of the time, so I needed to learn how to cook, or else you’d just starve,” he says, laughing.

As a film theory major, Aquino was drawn to the visual aspect of cutting film and thought he wanted to be an editor. That led to a PA job that he hated, which led to a gig helping to open the first Supreme store in Los Angeles (where he had been hanging out, commiserating about his PA job). Eventually, he landed in the finance department at the luxury art book publishing house Taschen, where he worked for over a decade, developing an eye for what he liked. Meanwhile, he continued to amass his cookbook collection.

At the end of 2018, Aquino kicked off Prospect as a six-week holiday pop-up inside his local coffee shop, Two Kids. At first, he sold a lot of new titles, akin to what you’d find at Now Serving and Vroman’s, in addition to books from his own vintage collection. But over time, he tweaked his sourcing strategy to make Prospect’s offering feel more like “a niche of a niche of a niche,” he says. When the spot next door to Two Kids became vacant in 2020, he started subleasing from the coffee shop, and Prospect became a brick-and-mortar with limited hours. Come June, Aquino will leave his job as an accountant at an interior design firm to focus on Prospect full-time.

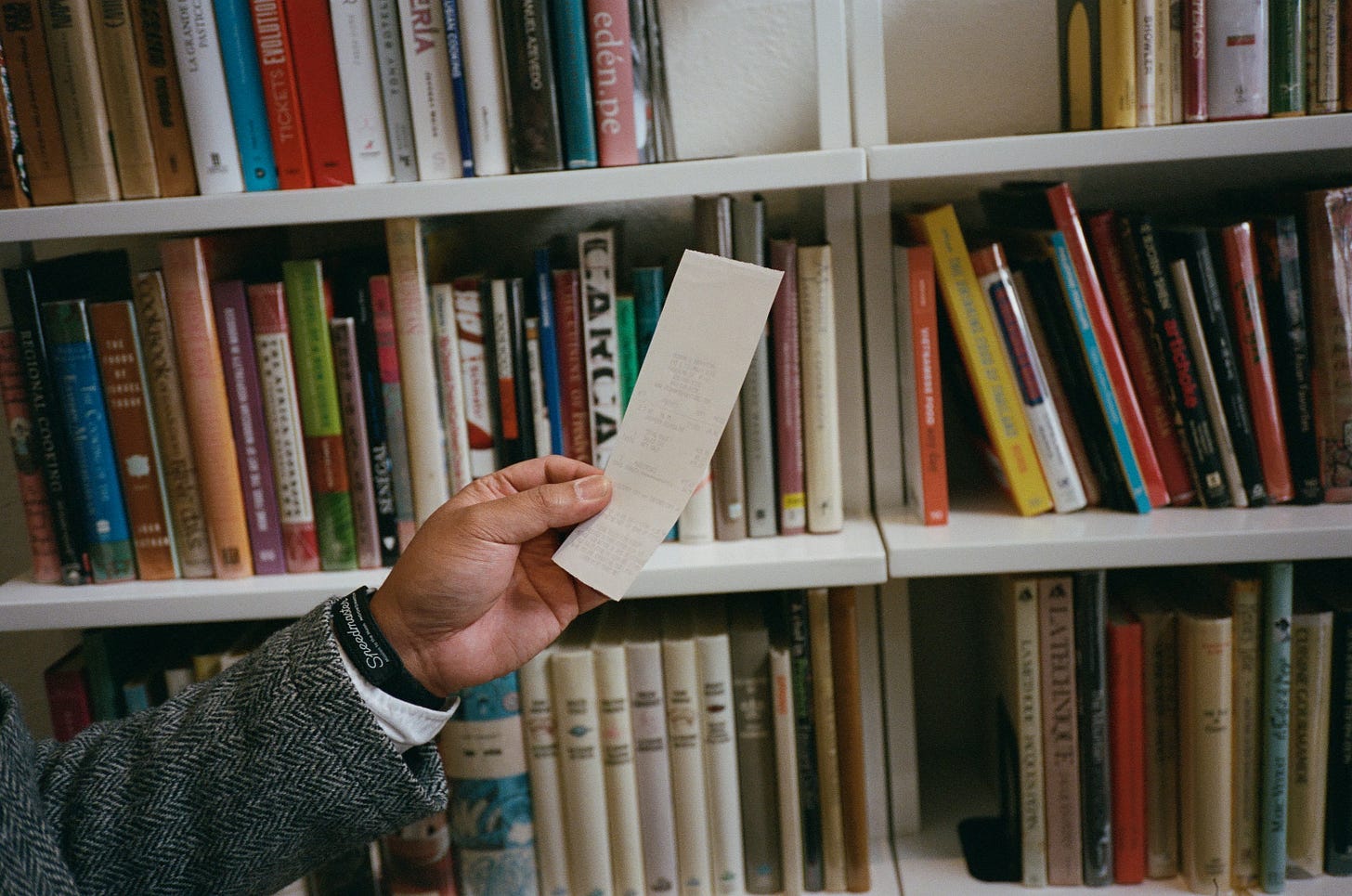

Today, Prospect is more like an antique store than a bookshop. And to that end, the experience is designed to be tangible. “The point is to discover something,” Aquino says. “If you have a cookbook in mind, I’m not going to have it. This is about seeing something you haven’t seen in a while or haven’t seen before. Because I can’t compete with the internet.” He designed his website without a search bar to resemble the feeling of browsing the South Pasadena shop. “It’s like Geocities from the 1990s,” he says. “I’m inherently old-school in that I think it’s all about having humans make suggestions for you, not the computer. Online, everything is so streamlined and easy, but to buy something in a bookstore, you have to get in your car or get on the train and make an effort. And there’s a memory to that book. You don’t get that with a click.”

“The point is to discover something. If you have a cookbook in mind, I’m not going to have it. This is about seeing something you haven’t seen in a while or haven’t seen before. Because I can’t compete with the internet.”

Aquino sources books from garage sales, estate sales, used bookstores, and online. Now that he’s more established, people who know about Prospect will contact him when they’re looking to sell their collections, including recently, the relatives of a late professor of Culinary Arts at Cal Poly Pomona. He likes to stock the Seinfeld script, written by Larry David, for “The Big Salad,” as customers love it. (It came with a DVD set back in the ‘90s, and many people discarded the book.) Ever-popular classics like The Zuni Café Cookbook and the Chez Panisse cookbooks always sell, too. “You can get them on Amazon, but I’ll carry them because they’re just terrific books,” he says. Most of what Aquino buys, however, simply appeals to him, whether it’s rare or not.

Value in vintage cookbooks can be found in first editions, limited releases, and author signatures, particularly of those who are no longer living (like Bourdain). For example, a pristine copy of the first printing of Julia Child’s inaugural cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, is worth almost $4,000 (the publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, did a cautious first run of only 5,000 copies). Prospect prices in accordance with other cookbook sellers, like Kitchen Arts & Letters in New York City and San Francisco’s Omnivore. When there is no reference, Aquino determines what he thinks is fair. “Sometimes, there’s just not a price with a book signed by Jean-Louis Palladin,” he says.

When Aquino worked at Supreme in the mid-aughts, he learned the importance of being a cultural shepherd—sharing knowledge with customers who didn’t quite understand what they were buying. For example, he wouldn’t just sell a Morrissey shirt to someone who wasn’t an obvious fan. “There were times where if we recognized that someone was interested in something, we would school them about who this person is and get them caught up as to why they’re on the t-shirt,” he recalls. “Instead of gatekeeping, you want to make sure that these things are passed down and taught.” This kind of cultural exchange within the realm of commerce doesn’t occur as organically online, which is why brick-and-mortar stores are so valuable. “You’re not in it to make money; you’re in it to meet people and share ideas,” Aquino says. “That, to me, is the payoff.”

It’s Sunday afternoon when we finish chatting, which means Aquino is about to close up shop and head to the market. While he’s at Prospect, in between conversing with customers, he’ll page through his books to find cooking inspiration for the week. On Sunday nights, he’ll often resort to Zuni Café’s famous roast chicken over bread salad or Sunday gravy from The Frankies Spuntino Kitchen Companion & Cooking Manual. “Today, I was feeling a little French,” he says. “So I looked in the Les Halles Cookbook. I’ll probably do the roasted veal short rib.”

I love your mix of photos + writing. Especially fitting because, imo, the best cookbooks include a lot of pictures.

This is incredibly dangerous information for me.