It’s Balo’s Time to Shine

If you know you know Balo Orozco, a singular chef with his own kombucha brand. If you don't, you will soon.

Photographs by David Gurzhiev

“Do you want some of this? Otherwise, I’m going to give it to them,” says Balo Orozco. The chef, who has a scruffy brown beard and tattooed arms, is standing in his Boyle Heights backyard with an oblong-shaped melon in one hand and a butcher’s knife in the other. At his feet, there’s a gaggle of chirping chickens and ducks. I shake my head, and he hacks the fruit in half. As he tosses both pieces to the ground, a ripple of nectar shimmers underneath the summer sun. “They love it,” he says, and within an instant, the fowl have descended upon the melon, briskly pecking their beaks into the sweet orange flesh, juice splashing everywhere.

Three years ago, he moved into a blue house a few blocks from the I-10. It came with a coop structure, and he hoped to have chickens eventually. But first, he planted trees—a nectarine, two lemons, a key lime, an apple, and two oranges—and started a garden. He roped passionfruit vines around the wraparound fence and began growing hoja santa, lemon verbena, bay leaf, rosemary, and basil to attract bees and ensure bounty. Then came the animals: a few chickens led to nine hens, one rooster, and four ducks, followed by kale, artichoke, Brussels sprouts, and mint to feed them, positioned around the coop’s perimeter. A giant bin of compost materialized, and a volunteer kabocha squash vine turned up.

At first, Orozco was living with his ex-girlfriend, Jacq Harning. The two met in 2019 while working at Onda, Sqirl’s short-lived Santa Monica sister restaurant, where he was chef de cuisine and she was a bartender. When the world shut down in the spring of 2020, they started a kombucha brand in an inspired impulse to preserve farmers’ market produce that would otherwise go to waste. They called it Sunset Cultures. A couple of years later, they broke up, and Harning left Los Angeles, but Orozco kept at it.

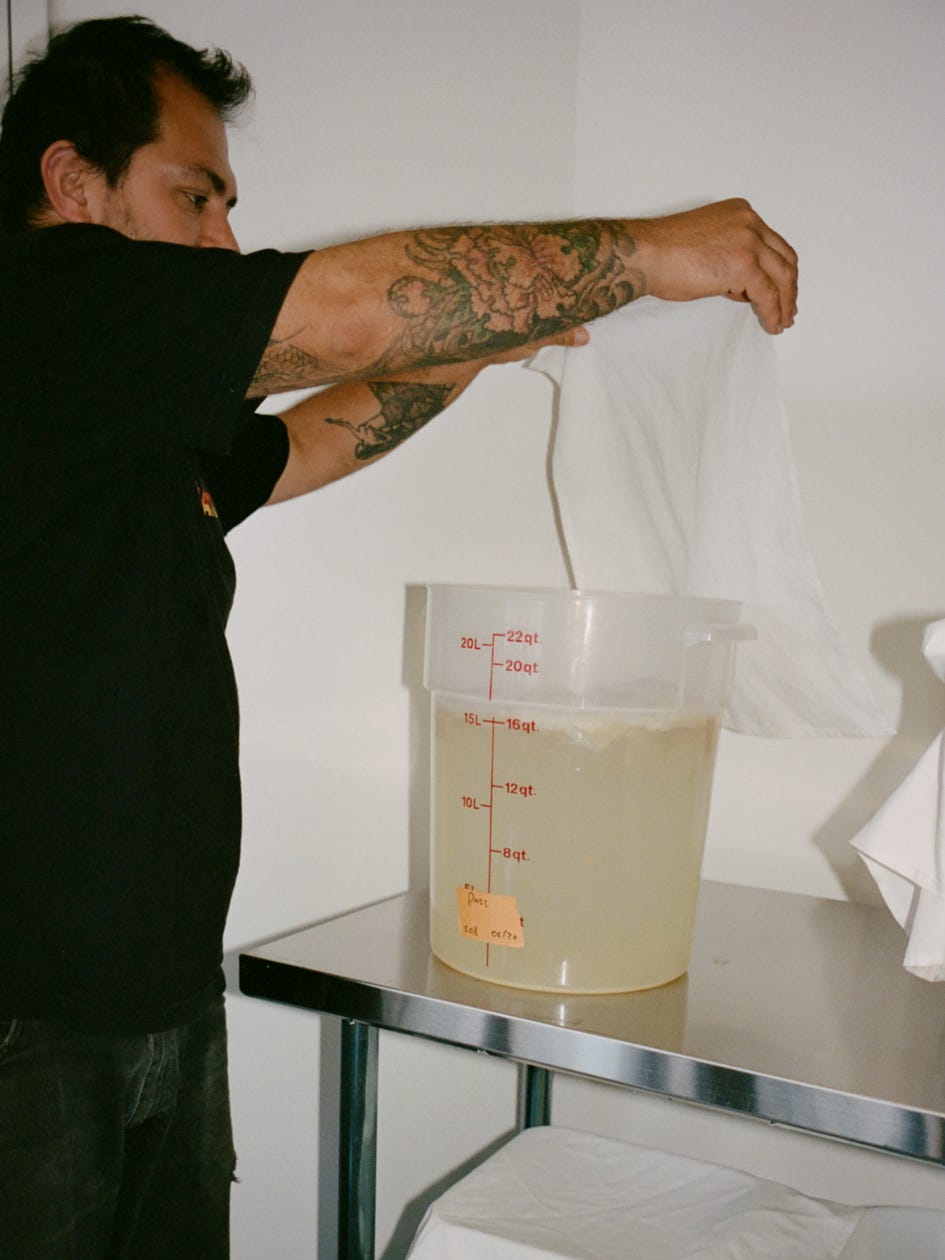

These days, you can find Orozco on Sunday mornings at the Hollywood Farmers’ Market. Walk several yards west from the market’s center point, and you’ll spot him on the right, hanging from the frame of his yellow tent as he navigates sales of kombucha and shrubs, wearing a t-shirt with a ripped-off neckline, denim pants, and combat boots. Otherwise, he’s both everywhere and nowhere. Ask any Los Angeles chef, farmer, café owner, wine person, shopkeeper, or food entrepreneur if they know Orozco, and most will smile and say yes. But ever since he tossed aside his chef whites after Onda closed early in the pandemic, the primary way to access his culinary finesse has been in liquid form, namely, fizzy fermented produce in a can.

Slowly but surely, Angelenos have caught on to Sunset Cultures. We’ve discovered their signature kombucha in flavors like cherry-fig leaf and passionfruit-lemongrass in stores and coffee shops across town, from El Sereno GreenGrocer to Topanga Living Cafe. And we’ve purchased four packs of their blueberry, moringa, and yuzu shrub at the farmers’ market. With a devoted fanbase secured and four years of fermentation know-how, Orozco is confident that the time is ripe for a revamp. In a few weeks, he’ll shed Sunset Cultures in favor of a new name for the brand. Those fruity and aromatic concoctions that impart a pleasant bodily buzz while tasting like wild California? They’re now, like him, called Balo.

Balo will remain in stock everywhere Sunset Cultures was before—at Café Tropical, Honey Hi, and L.A. Grocery & Café, for example, and on tap at El Prado—sporting a fresh, sleek look courtesy of Scott Barry, a designer known for his work on Sqirl and Rose Delights. More than a makeover of Sunset Cultures, the shift is a way for Orozco to hone his personal brand once and for all. As Balo, he can present as everything he is—chef, fermenter, gardener, host, waste wiz—all at once.

More than a makeover of Sunset Cultures, the shift is a way for Orozco to hone his personal brand once and for all. As Balo, he can present as everything he is—chef, fermenter, gardener, host, waste wiz—all at once.

Orozco was born and raised in Guadalajara, Mexico. From a young age, he knew he wanted to cook. Because his mother was often working and his father was often traveling, he was responsible for feeding his younger sister, and he took a liking to the task. When his father was home, he’d invite a bunch of family and friends over and cook for everyone. “I always liked the idea of gathering people,” Orozco says. By the time he was 16, he was working in professional kitchens, first at the Japanese restaurant Suehiro and then at an Italian restaurant, where the owner was generous enough to pay for half of his culinary school tuition.

After graduating, he went to Tulum on vacation and decided to stay. It was 2010, a few months after Hartwood—an off-grid, open-air restaurant with market-driven cuisine cooked over live fire—had opened. He stopped by for a beer and a snack and met Eric Werner, Hartwood’s chef-owner, who was looking for someone to help him run the kitchen. “I was like, ‘Okay, maybe I’ll just work here for a few months,’ and then I was there for five and a half years,” Orozco says.

Hartwood eventually became a bona fide sensation, winning over the hearts of globe-trotting gourmands and renowned chefs such as Noma’s Rene Redzepi. It also proved to be incredibly influential on Orozco’s cooking style and his interest in sourcing quality local ingredients and combating waste. At Hartwood, there is no ceiling, no walls, no gas, and no electricity, just a tiny generator and a solar panel to power the restaurant’s lights. “It was a very small town at that time, so the farmers would come and offer produce and pork door by door,” says Orozco. He became good friends with an Argentinian farmer, Julian Lovaglio, who taught him how to use compost to create a closed-looped system. On the days that Hartwood was closed, he spear-fished and cooked big dinners for his friends at home. Meanwhile, chefs from all over the world came to Hartwood to do events, including the poster child of open-fire cooking, Francis Mallmann, whose executive chef, a woman, cooked an entire cow over the course of 24 hours, subsequently blowing Orozco’s mind. “She served it with spoons, it was that tender,” he recalls.

Today in Los Angeles, Orozco has become quietly known for his predilection for and proficiency in cooking over fire. When hired for private events, he’ll grill tomatoes and tomatillos to make charred salsas, wield huge slabs of meat and whole fish over flames, and always serve fresh tortillas on the side. For the Malibu wedding of Honey Hi founder Kacie Carter Chamberlayne and writer-filmmaker Brian Chamberlayne, he roasted nine whole lambs and 23 chickens on a dome-shaped metal apparatus. For a Nike collaboration inside The Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, he turned his fiery ambitions towards a bounty of fruit, fish, and vegetables.

After leaving Tulum, he hopped around from Mission Cantina in New York City to a brief stint in Ensenada and ultimately landed in Los Angeles. He clocked in at Night Market Song, Redbird, and Madcapra, the now-closed falafel stand in Grand Central Market that evolved into Kismet. There, Orozco met Jessica Koslow, who hired him to run events at Sqirl, and that couple-year stint turned into his next job, rejiggering the entire waste system at Wolfgang Puck’s 300-person catering outfit. One person trying to create change in an organization of that stature proved impossible. Still, Orozco didn’t give up on working with waste. “It’s more exciting than cooking a steak,” he says.

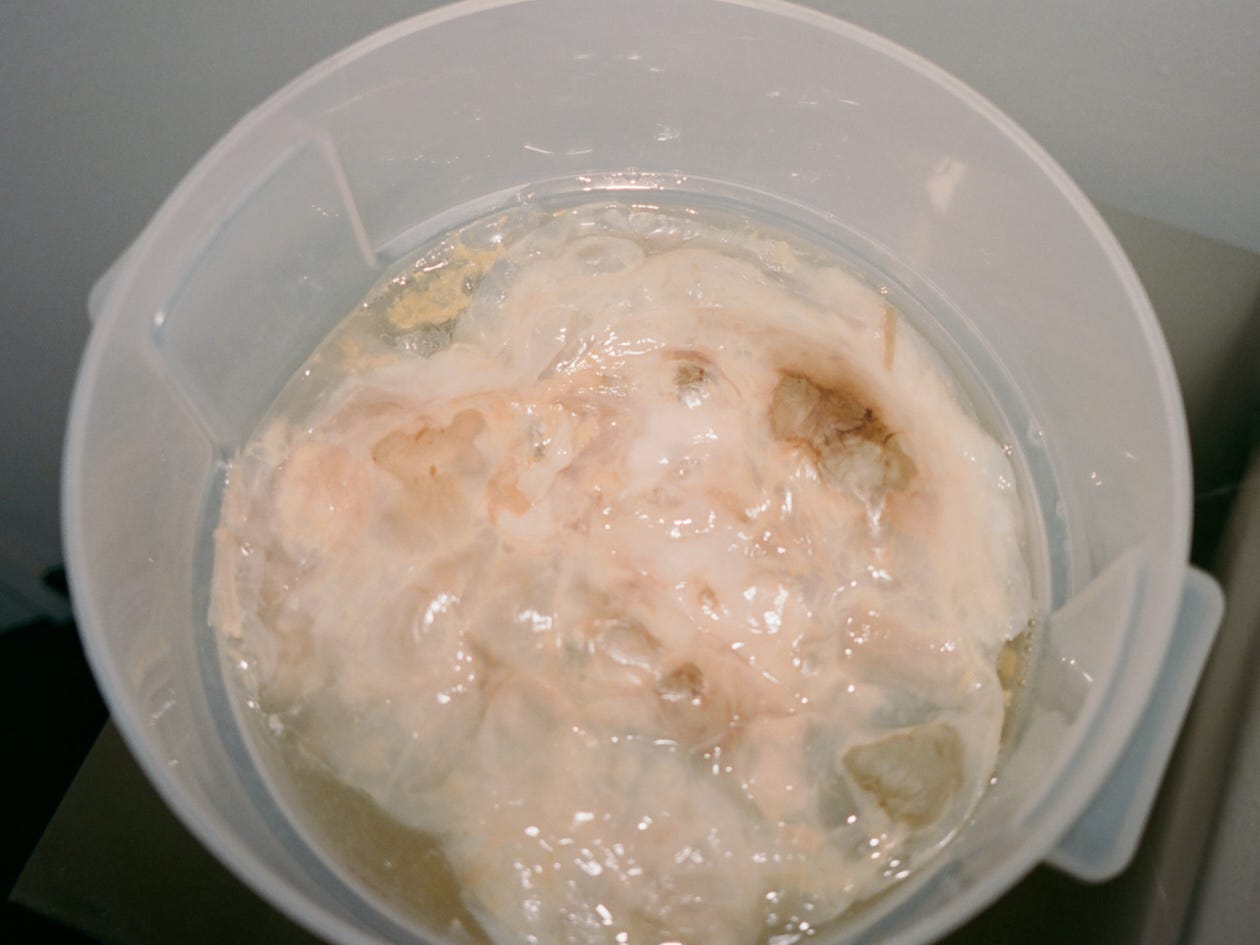

Fast forward to the spring of 2020. COVID-19 loomed large, restaurants closed, farmers scrambled to figure out what to do with their excess produce, and Orozco and Harning wanted to help. Harning had been focused on nonalcoholic beverages at Onda, so she had some experience making kombucha. Together, they preserved as much produce as humanly possible, learning by trial and error. They canned tomatoes, pickled cabbage into sauerkraut, made nectarine vinegar, and produced kombucha in a rainbow of fruit-forward flavors. They delivered their goods to Angelenos at home and started stocking local shops. And they solidified deep, lasting relationships with farmers, including Alex Weiser of Weiser Farms, Rick Dominguez of Ricks Produce, and Roland Tamai of Tamai Family Farms. By the end of the year, they had decided to focus on kombucha and then tackle shrubs next.

“It was so much work, without equipment, without anything,” Orozco says. “We’d get frustrated because some of the bottles were good, some were bad, some tasted terrible, all in the same batch.” When Harning left L.A. in early 2022, he considered shutting down operations entirely, then thought better of it and doubled down. He leaned on Matthew Xavier Garcia of Homage Brewing to gain a deeper understanding of carbonation, which motivated him to switch from glass bottles to more inexpensive cans. And he dialed in his product line at his commissary kitchen while keeping his door open to farmers with excess or damaged produce to inspire new experimentations. “I could tell the product was getting better, little by little,” he says. “And that was exciting.”

As he gears up to slap his name on his cans and step into the limelight, Orozco takes a moment to consider how far he’s come. “Lately, I've been feeling a lot more happy with the product,” he says. “Like, very, very happy.” He’s working on collaborations with wineries like Good Boy Wine, restaurants like Zuni Café, and brands like Diaspora Co. He’s testing a coffee kombucha made with beans from Canyon Coffee and a mix of citrus. He talks about making wine bottle-sized Balo to sell in wine shops. But he’s not looking to get too big too fast. “Because then it won’t be fun,” he says. Naturally, the fun includes cooking, too. “Before, I thought I had to just focus on making kombucha, but then I’d miss cooking. I do private events at least once a month, and I want to do something more open to the public. [Balo] is a way for me to do everything together,” Orozco says. “It makes sense.”